A group of Inuvialuit youth in Canada’s High Arctic have a message for climate change deniers across the world: “It’s happening to us!”

For as long as she can remember, Carmen Kuptana has been travelling across the wind-packed snow of the Beaufort Delta with her family. At the age of 17, she has already seen more of the surrounding area than the animals that call the region home. Using the land to access traditional hunting and fishing grounds, Carmen says it’s becoming easy to spot the changes in the environment around her.

“We still go to the same places, but it’s [for] like less and less time each year,” she says. Tuktoyaktuk is located in the Northwest Territories, on the coast of the Beaufort Sea. One of six communities in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, it was a hub for oil and gas activity in the 1970s. Fewer than 900 people call it home, and they are all seeing the obvious changes to the land.

Just down the road from where Carmen lives is her cousin Nathan’s house. As is the case at many households in Tuk, snow has drifted over the old snowmobiles in his yard. But Nathan is always ready to hunt when the call comes.

Nathan says his hunting trips take longer than they used to, due to changes in the ways he can travel. Warmer weather patterns mean shorter ice seasons. Some channels and rivers are no longer accessible.

“It’s becoming harder to predict the weather at certain times of the year,” he says. The people of the region aren’t the only ones affected by the changing lands and weather conditions: Nathan says the migration patterns of local animals have also been shifting—another reason his family needs to travel farther out to hunt.

Each of the seasons has been changing; Nathan watches to see how the animals are affected.

“We see it all over—like, we are getting salmon around Tuk now,” he says. He explains that trout and char are the fish typically found around the community. Salmon wouldn’t usually be found this far north. Many things are changing.

The Start of Something New

Historically, the Inuvialuit have shared their stories orally within their communities. But in recent years, northern society has seen a shift to sharing knowledge with a wider audience, through video and online outlets. Both Carmen and Nathan are interested in learning new skills and sharing their stories, so, when Tuk’s Mangilaluk School offered an opportunity to learn filmmaking, they jumped at the opportunity.

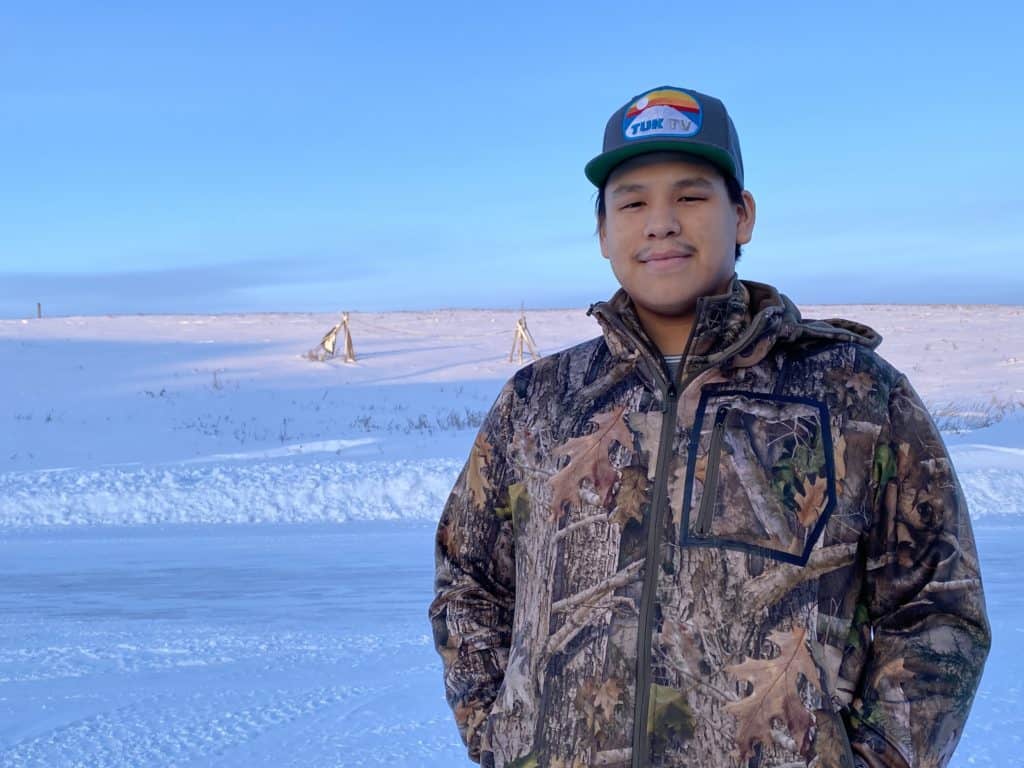

The cousins were joined by a few youths from around town, and what started as a school-based media program soon grew into a full video workshop aimed at teaching young people technical skills in camera Top to bottom: Nathan Kuptana, Darryl Tedjuk, Carmen Kuptana (L), Eriel Lugt (R) operation, video editing and interviewing. Darryl Tedjuk and Eriel Lugt were two of the others who joined together to form a new art collective. Working with the help of visiting professionals Maeva Gauthier and Jaro Malankowski, they found a name—Tuk TV.

Now that these talented young minds were gathered together and had defined a purpose, they needed a direction.

“We started by identifying issues and problems we see in our community,” Nathan explains.

They identified a few social issues as possible topics—like microplastics in the ocean and cultural differences—but the one that they all agreed would come first was climate change.

With the help of Gauthier and Malankowski, the collective learned how to operate cameras, capture proper sound levels, conduct interviews for documentary films, and edit and produce a short doc.

For Eriel Lugt, who is also 17, the workshop provided some much-desired technical background, to complement her growing interest in photography and art.

“I’ve always liked taking pictures, so learning how to edit was really fun,” she says. Once the group finishes their current projects, Eriel plans to take her new interests and expand her work to tell her own stories from her perspective. “I want to show the beauty of other places and learn more about journalism.”

Once the youth had started to learn new techniques, they found they wanted to meet more and more, to take in as much information as possible. They began meeting a few times a week during the last spring session of their school. When classes were done for the summer, they met even more often.

In order to get the shots they needed for the documentary, which they had decided to call It’s Happening to Us, the group needed to get a better view of the whole region. Before long, they found themselves flying over Tuktoyaktuk and the coast of the Beaufort Sea in a helicopter. “I got to see different parts of the land I didn’t see before,” Carmen said about the experience.

Learning from researchers and other professionals in the field was one of the more hands-on elements of making the film for the group, as they saw the slumping effects of erosion firsthand. Not all the information on the changing conditions of the land came from academia, however, as many of the stories they tell in the documentary come from local elders who have spent their lives travelling in the region, and who shared their traditional knowledge for the project.

Northern Exposure

It’s Happening to Us has already brought Tuk TV international success. In late 2019, the filmmakers were invited to screen it during the COP25 United Nations Climate Change conference in Madrid. The trip to Spain was unforgettable—Eriel said it was the farthest she had ever travelled, and that she enjoyed seeing more of the world.

“Our families were very proud that we showed our film there, and it showed multiple times,” she said.

The group insists that, even though the film has been screened, it is still not complete. There are plans to expand the 20-minute version into a feature-length documentary, and to include more stories from across the Inuit region.

Tuk TV has already been in contact with other youth across the Arctic who share similar stories. This project, and the workshop that started it all, are just the beginning for this group of bright young minds from the coast of the Arctic Ocean. The experience has left all of them with an invigorated sense of motivation to do big things in their lives, and empower their own communities.

Carmen and Eriel agree their new skills will help make them better leaders in their community.

“I see kids who don’t care, but I want us to live how we used to,” says Carmen. “I want more youth to get into hunting and speaking our language.” Carmen wants to tell stories about the Inuvialuit way of life, to promote it to others, but also to those who live in her community. “I just want to make a difference, and I think filmmaking is a good tool for that,” she says.

Nathan, meanwhile, sees a future for himself in journalism and will take his new interests as far as he can. “I want to bring this filmmaking further,” he says. “I see myself at the CBC or something.”

For Darryl, the workshop is a way to grow his leadership skills and use them in his hometown to strengthen his relationship to his culture. “I see myself as a leader here,” he says. Looking over the harbour from his house, Darryl says the traditional ways are still very important to him and hopes he can continue his way of life, while using his new confidence and ability to tell stories in ways only he can.

For Darryl, the workshop is a way to grow his leadership skills and use them in his hometown to strengthen his relationship to his culture. “I see myself as a leader here,” he says.

Looking over the harbour from his house, Darryl says the traditional ways are still very important to him and hopes he can continue his way of life, while using his new confidence and ability to tell stories in ways only he can.

For now, the group has returned to their studies to finish off another year at Mangilaluk School in Tuktoyaktuk—but only time will tell where their next projects take them. Tuk TV is ready for action.