By Chelsea Kowalski

This article is reflective of the abilities and features of AI chatbot technology at the time of publication.

At the time of this writing, artificial intelligence (AI) is basking in the glow of an enormous spotlight. Initially seen as a concept of science fiction, AI—the simulation of human intelligence by machines—has come to mesmerize people all over the world. Millions of people are using AI software programs to help problem-solve, create content, or just have a conversation.

AI technology can do amazing things that humans don’t have the ability to do themselves. It can process information faster, detect patterns more easily, and analyze more data in a fraction of the time people need to execute these processes. And yet, most of what AI is being praised for right now is a trick.

AI chatbots cannot judge or think or form opinions. They can, however, make you think they can.

AI technology is often described as a “thinking” computer. While it can certainly seem like an AI chatbot like ChatGPT is engaging in thought when it provides responses to a user or synthesizes original content to come up with something new, the machine is really just following instructions in a code. Still impressive, but not representative of the actual ability to think.

What is ChatGPT?

ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI, is arguably the most popular chatbot in the current market. It is currently available in two iterations of OpenAI’s large language model (LLM) technology, GPT-3.5 (free) and GPT-4 (paid). ChatGPT reached more than 100 million users in the first three months since its release, and is being used for a wide array of tasks, including creating résumés, solving mathematical problems, debugging code, and writing essays. But a product with so many capabilities comes with just as many risks and dangers. One such risk is plagiarism.

AI-created content is generally advertised as original content because the technology assesses and extracts from many sources, bringing them together to form a cohesive text, just as a student might review various sources before writing an essay. When a student looks up sources of information for an essay, however, they are learning at the same time. They are absorbing material, making connections among various pieces of content, and then (hopefully) developing their own thoughts about the essay prompt. Close reading, conducting research, critical thinking, and reasoning skills are among the most important elements that a student learns. Passing off that work to AI not only takes away the opportunity for skill development but also guarantees the work they hand in won’t have any original thinking or reasoning, as AI chatbots are incapable of performing those tasks.

Understandably, to avoid issues of plagiarism and missed learning opportunities, many educators discourage student use of AI. To remain accessible and permitted in most classrooms, AI will need to function as an educational tool or perhaps even as a tutor. Khan Academy, an educational organization, understands this. Its founder, Sal Khan, recently came out with Khanmigo, an AI-powered tutor for students and an aid for educators. It acts as a pop-up chat feature that encourages and aids students in their learning process. Khan admits that this chatbot sometimes generates inaccurate answers but stresses that its role is that of a coach and not of an expert. For educators, Khanmigo is advertised as a teaching assistant to help produce lesson plans or classroom activities.

Google AI came up with its own LLM (called PaLM 2) and a chatbot named Bard. Its way of dealing with the ethical dilemma of producing content that is derived from existing content is to advertise Bard as an experiment. In fact, Google openly admits that Bard “may give inaccurate or inappropriate responses.” While the discussion about AI often jumps to very complicated tasks with serious implications, Bard subtly takes a backseat approach, calling itself a “creative and helpful collaborator” that can assist the user in simple tasks, like creating lists, brainstorming, or drafting emails—more of a “complementary experience to Google Search.”

Khanmigo, an AI-powered tutor for students

and an aid for educators, from Khan Academy

Bard’s simplicity extends to its citations. If Bard uses a direct quote from a web, the webpage is cited. Otherwise, the content generated by Bard is considered original. But its honesty and experimental status is also what makes it lag behind its competitors. When a user asks Bard to explain how Bard itself works, it has trouble answering the question accurately. Ironically, Bard’s self-reflexive attempts to explain how it functions is one of the prime situations that can lead to misrepresentation and misinformation. Google explains that Bard, as an experimental program, is still flawed and can often make false claims about itself.

So, how can AI be helpful for educators and students?

Open communication is key. Many students already know about AI technology and are already using it, whether or not it’s encouraged in the classroom. To pretend it is not in active use simply creates a situation in which students will use it inappropriately and without proper limits. With careful consideration and an understanding of chatbots as tools to supplement primary forms of education, AI can be used with a learning-first approach.

Giving students the chance to explore this technology can make a big difference in the way they learn to use AI and allow them to develop skills for AI technology usage. For example, students could ask a chatbot to write an outline or even a first draft of an essay, with the understanding that it is then their job to fact-check, revise, and write the final draft. Alternatively, students might engage in conversation with a chatbot to ask about its thoughts to show that AI cannot generate opinions, only share information (sometimes inaccurately). Incorporating AI exploration into existing lessons can invigorate learning experiences and show learners how to use AI as a supplement rather than a replacement.

Ten years ago, it was relatively common to encourage students to learn mathematics by demonstrating the many potential functions of those skills in real life. Before smartphones, it was common to have a math teacher insist that certain math skills were necessary because no one carries a calculator everywhere they go. Of course, nowadays that argument doesn’t work. So, teachers have adapted. Today, using a calculator is seen not as an act of defiance or laziness but rather as employing a useful tool. In fact, it would be seen as a detriment for a professional not to know how to use a calculator. The same process of evolution will happen with AI. As its use grows, students will continue to integrate it into their daily lives and the ways they learn. Imagine the learning opportunities that could be a part of every classroom if educators sought to mirror this absorption of this technology.

The Turing Test

Simply put, the Turing Test determines whether a machine can convincingly act as a human. The test participant engages in conversation using a device that is connected to both a person and a machine. After the conversation is completed, the participant is asked to determine which conversation involved the human and which involved the machine.

To date, no AI chatbot has been able to pass the Turing Test. AI technology is evolving rapidly, though. Humans are evolving as well. The average online user has completed some version of the Turing Test, thanks to the internet and the rise of bots. Social media apps have made it easy for bots to friend, follow, or send direct messages to the average user. Bots in current use aren’t so advanced that they can easily masquerade as a human on the other end, however. But, AI chatbots might be a different story.

Can we discern content created by a human from similarly themed content created by AI? You can try now. The following two paragraphs are responses to the same prompt. One was written by a human and one by ChatGPT (GPT-4).

Were you able to determine which paragraph was written by the AI? If so, congratulations! AI has made considerable progress in the last few months in its ability to represent thought processes and mimic human writing and responses, but of course, it’s still not an exact replication. AI tends to provide better answers to prompts that require facts rather than opinions. If the prompt had been, “Which colour is the best?”, it would be fairly easy to tell which paragraph was written by ChatGPT. ChatGPT would not give a convincing or definitive answer, as the question demands subjectivity and a definitive answer requires thought and judgment.

Beyond the arguments regarding plagiarism and critical thinking skills, one of the more compelling reasons against leaving all the writing to AI is simple: emotion. When we read and research and learn, we feel emotions and writing is one way we can express them. A computer can’t feel. It can only be programmed to act as though it does.

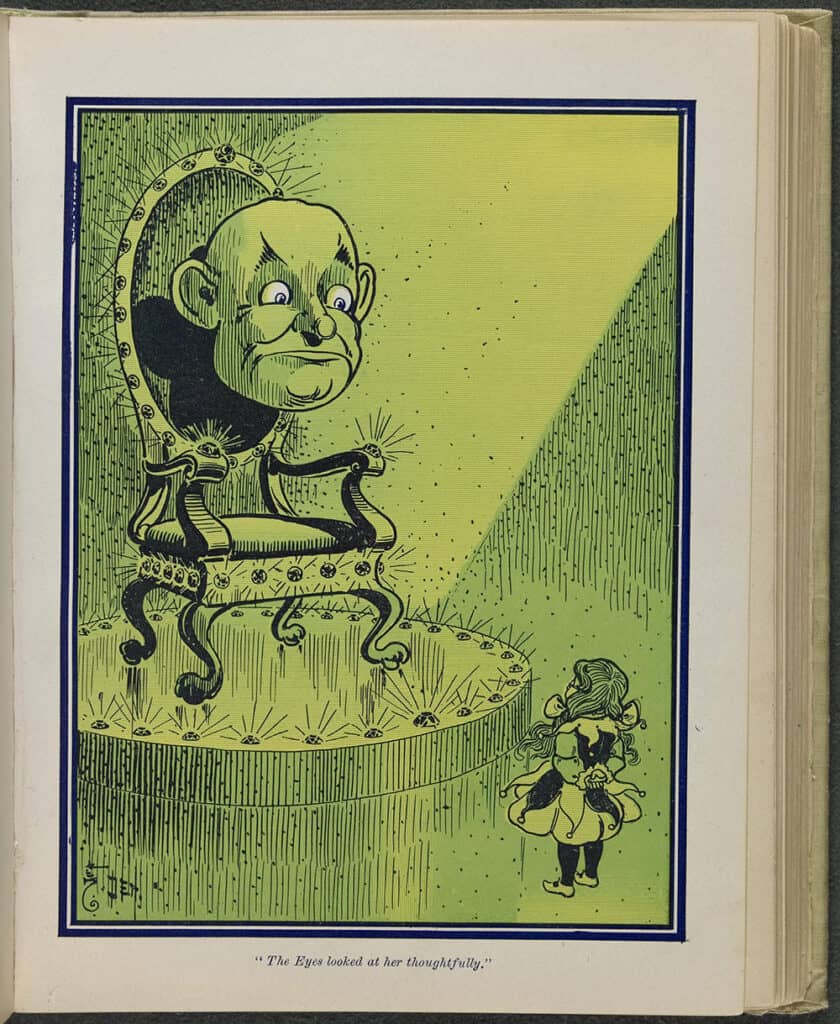

AI is an illusion. AI chatbots are being portrayed as thinking machines but they aren’t there yet. We humans are still the thinkers; AI is merely the medium. AI cannot create anything without human thought behind it and, when it tries, it very often delivers an inaccurate product. For now, AI can be thought of as the wizard from The Wizard of Oz. Great and powerful, yes, but there is most definitely a person behind the curtain.

Paragraph A was written by ChatGPT.