By Caroline Whittle • Photos Courtesy of Caroline Whittle

Born and raised in Iqaluit, I grew up speaking both Inuktitut and English at home. I was always reminded to speak Inuktitut as much as possible as a child. My mother would refuse to speak in English—and still does to this day—unless necessary. When I was younger, I couldn’t understand why, but today, I see her perspective clearly, having lived in a world in which Inuktitut is hardly spoken. As an Inuk, I have always been proud to speak my language; simply speaking Inuktitut, however, is not enough. A language requires maintenance by the individual as well as by the community at large.

In 2021, I completed a Certificate in Indigenous Language Revitalization at the University of Victoria. This program explored Inuktitut and Inuit history since we used oral methods of representation and storytelling to the time of colonization, when Inuit were forced to adopt a writing system of syllabics, which is still in use today. This was a place to dig into the roots of our ancestral background and it allowed us to picture the world our ancestors lived in with just Inuktitut as their language. I felt regret that I missed out on an opportunity to thrive in an environment imbued with Inuktitut and even more regret for the next generation who are separated from our language even more. Learning traditional words—that only our Elders knew—was a revitalizing experience that pushed me to preserve what Inuit have and promote what we can learn for the future.

Classrooms are not the only place this kind of learning can be achieved. From 2015 to 2022, I worked with the Parks and Special Places division of the Government of Nunavut. I was a part of the “Learn to…” programming, which held outdoor programs about Inuit culture in the summer and fall in Iqaluit Kuunga (formerly called Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park). This was the most popular programming, which taught participants the importance of knowing the Inuktitut names of local plants, as well as their medicinal and nutritional uses. The opportunity to pass down this knowledge promoted and preserved Inuit culture alongside our language. Having Elders pass down years of knowledge proven to be beneficial over and over is what brought us here today as Inuit. There is such a hunger to learn from Elders, and in a place like Iqaluit, it’s important to make that learning accessible. These outdoor lessons were a way for us to bridge science education, Inuit culture, and language learning. Everything is connected to nature and to science, and this is represented in our language. Everything is connected.

Iqaluit Kuunga

Iqaluit Kuunga Participants learning about traditional plant uses in Kimmirut

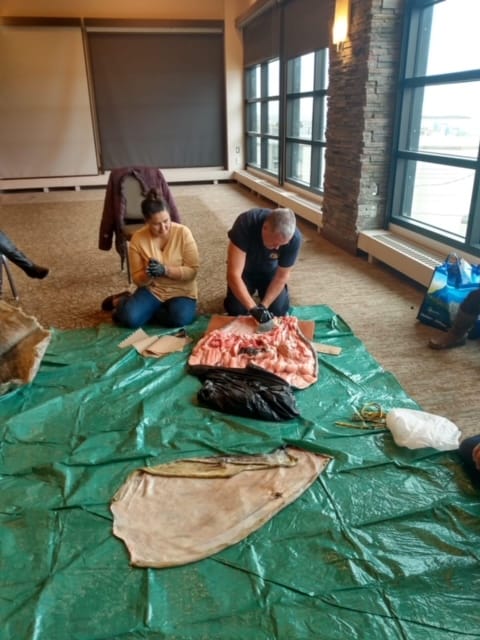

Participants learning about traditional plant uses in Kimmirut Learning to clean sealskin in a cultural session

Learning to clean sealskin in a cultural session

Suputiit (Arctic willow) is best picked in September for the wick of the qulliq (stone lamp)

Suputiit (Arctic willow) is best picked in September for the wick of the qulliq (stone lamp) Making a kakivak (traditional fishing spear) in Iqaluit Kuunga

Making a kakivak (traditional fishing spear) in Iqaluit Kuunga

As an educator, I see that there is a real struggle when learning Inuktitut. For a while, the question has been, “What are we doing to change this?” But I believe this question should be: What aren’t we doing? Those growing up today are facing a very different world than before, even in our own territory. Everything we see and hear is in English first. Support for English-language education, as opposed to Inuktitut, is far greater and publicly acknowledged despite both English and Inuktitut being recognized as the territory’s official languages. Our government, our schools, and our community leaders need to push for better representation so we see and hear Inuktitut everywhere. We need to look through an Inuit lens and offer support in getting our language back into the minds and mouths of our people. We need to come together as Inuit educators and leaders to promote our language through programs and courses like those I’ve mentioned here. The power of learning is something no one can ever take away. We are living in a fast-evolving world, where it can feel like there is no place for our language. We need to speak it anyway—and loudly. Speak it, sing it, read it, write it, use it, and be proud of it.