How Art Can Change Our Relationship to the Natural World

By Sofia Osborne

Tania Willard

When Tania Willard was growing up in the small town of Armstrong, British Columbia, she knew she was interested in art, but the path to becoming an artist felt unclear. It wasn’t until she was mentored by Syilx Elder and artist Barb Marchand and the late Secwépemc artist Dave Seymour that she began to think of a future in art.

Now, Willard is an artist, curator, and assistant professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC), Okanagan. A mixed Secwépemc and settler, Willard’s research is focused in part on providing a view of the art world in small towns, rural centres, and on reserve.

“I’ve had to really think through what art is in a western context, and how that has been divorced from a lot of Indigenous ideas of art,” she says. “That’s really the focus of my practice … the overlaps, the intersections, and the omissions between those kinds of art practices.”

When her first son was born, Willard decided to move back to the Neskonlith Indian Reserve, where her father lived, so her son could be surrounded by Secwépemc culture, language, and land.

“That was a big move, because a lot of how we think about arts and culture [revolves around how it] functions in urban centres in Canada,” she says. “We have different forms of arts and culture that are active and beautiful and inspiring and enduring on a reserve, but they’re not positioned in the same way.”

Thinking through that inequity, while at the same time reconnecting with the beauty of the land and the way Secwépemc forms of art are born from land-based materials, led to a shift in Willard’s work.

“I really wanted to reposition and recentre the work. Instead of asking to come in the door and show Indigenous art, I wanted to shift that centre completely and say, ‘Our art is valid, our land is central’,” she says. “If I think through an Indigenous-knowledge-based way of working, then the real gallery is the land.”

For Willard, rather than trying to fit into a western, urban model of art, it’s been much more generative to reject that path and carve out her own space. Part of that work has been through the creation of BUSH Gallery, a collaborative project with Tahltan performance artist Peter Morin, Vuntut Gwitchin artist Jeneen Frei Njootli, and Métis artist Gabrielle Hill. The gallery is a radically re-centred approach to art-making, situated on reserve, which grew from imagining a space for art and connection outside of the overly westernized institutions for art.

“It has this reach that is addressed by a simple question … How do we see art galleries? How would we, as Indigenous Peoples, create, or how do we create, spaces to think through and appreciate art?” says Willard.

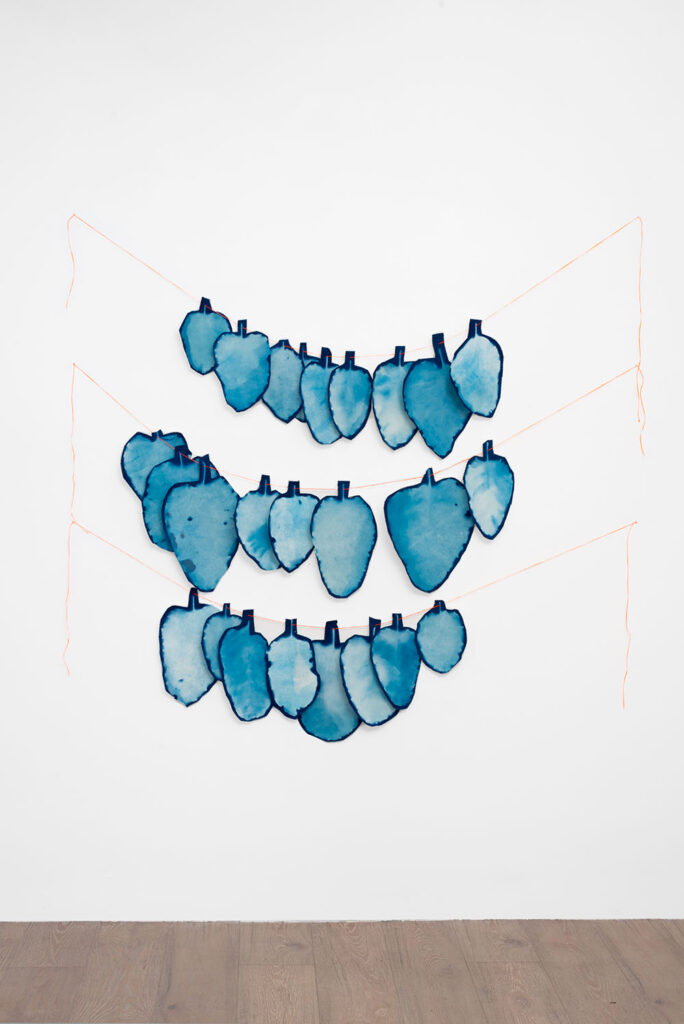

Willard’s exhibition Sensitized, hosted at Pale Fire Projects, features Carriers, sun prints, an anthotype, and images of baskets from collections of Secwépemc and interior Salish artworks.

Willard’s exhibition Sensitized, hosted at Pale Fire Projects, features Carriers, sun prints, an anthotype, and images of baskets from collections of Secwépemc and interior Salish artworks.

Courtesy of Pale Fire Projects

Inspired by the abundance of the land, Willard’s art incorporates practices like hide-tanning and basketry, to collaborations with nature, like sun-printing, an alternative photographic process that requires exposure to the sun to develop.

A recent exhibition of Willard’s work at Pale Fire Projects called Sensitized, which she created in mid-2023, brought together her interests in archives, Indigenous resurgent acts, land-based work, and lens-based media. The exhibition included sun prints from the leaves of tobacco plants she grew, images of baskets from collections of Secwépemc and interior Salish artworks that are in museum collections—often unnamed and unacknowledged—and an anthotype she created using harvested wild berries to develop an exposure mimicking smoky skies.

Willard’s Carriers.

Willard’s exhibition Sensitized, hosted at Pale Fire Projects, features Carriers, and sun prints.

Willard’s exhibition Sensitized, hosted at Pale Fire Projects, features Carriers, and sun prints.

Willard’s Carriers.

Courtesy of Pale Fire Projects

The exhibition also included a new sculptural work called Carriers—a series of Rubbermaid bins Willard stitched over with leather, rope, sheep rawhide, cedar root, and other materials to make them resemble birch-bark baskets. Drawn from her experiences with wildfire haze and threatening winds, Willard’s art formed a response to the need to be on constant alert during wildfire season. In addition to the materials, Willard’s skills in basketry, taught to her by Elder Delores Purdaby, a master artist in basketry, were a part of the art she created.

“As part of relearning those skills, and that relationship, that artistic process, it’s not just the skill of doing it, it’s also knowing how to harvest, having a relationship to the land around me, and being in reciprocity. So making an offering, harvesting, knowing how to work the material, and then also knowing yourself in order to work it,” she says. “We have many teachers in the land.”

Ultimately, Willard wants to encourage young people to express themselves in ways that nourish them.

“It’s for our health, it’s our rights. It can continue the traditions of our ancestors, and extend the continuum of land rights. And that’s so important. And it’s also a way of us connecting to each other, and to the lands around us. And that includes all of us,” she says. “Because after all, we all need to nourish each other and the land to live together.”

Holly Schmidt

As an artist, curator, and educator, Holly Schmidt is trying to put a frame around something that is often taken for granted: the natural world around us.

“Ultimately, the goal is really to have people, through their attention, actually begin to care about all of these living beings and about their relationship and interaction with the natural world,” she says.

For the last five years, Schmidt served as the artist-in-residence at UBC’s outdoor art program, a residency she called Vegetal Encounters, which ended in fall 2023. Rather than being focused in the visual arts department, her work reached broadly across campus, engaging students and faculty from many disciplines around the theme of human relationships with plant life.

Artist Chrystal Sparrow holds a sketch created in the workshop.

A summer 2021 participant of Holly Schmidt’s slow walking workshop sketches in the fields at Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Courtesy of Rachel Topham Photography

“I really saw myself working in a very plant-like way, or a kind of rhizomatic way,” she says. “I could send these roots and tendrils out and create networks and connections between many of these disparate departments across campus.”

Inspired in particular by Potawatomi ethnobotanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, Schmidt wanted to explore the ways plants can teach us and how we can learn from plants.

“Being on the unceded territory of the Musqueam people, I just gained such an incredible appreciation for the significance of plant life on campus; how it’s really a shared responsibility to care for that plant life and imagine new ways of considering it,” she says.

One of Schmidt’s projects, called Fireweed Fields, transformed the grass lawn outside UBC’s Belkin Art Gallery into a plant meadow, with a particular emphasis on fireweed. As we find ourselves in a time of climate crisis, Schmidt was drawn to fireweed as it is one of the first plants to come up after a forest fire.

Artist Holly Schmidt spreads a seed mixture for the planting of her project Fireweed Fields in fall 2022 at Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Schmidt, Fireweed Fields, artist’s rendering.

Participants in the planting of Fireweed Fields.

Schmidt’s Fireweed Fields project being planned out.

Top left, Bottom left and right: Courtesy of Nigel Laing

Top right: Courtesy of Holly Schmidt

Fireweed also holds deep significance to the Musqueam Nation. The Musqueam Environmental Stewardship Department advised and worked with Schmidt on the project, helping to develop the fields into a full and abundant meadow.

“Fireweed provides shelter and sustenance, so it provides a kind of care for other beings around it. And it’s really the beginning of a new sort of ecosystem,” she says. “I wanted to think about fireweed as this plant that has the potential to bring new life, a kind of resurgence of life, back to campus.”

As an artist, Schmidt has always been intrigued by the sciences, and she met many scientists on campus who were open to, and enthusiastic about, her work. She brought environmental science and biology students into Fireweed Fields to do observational drawing, encouraging them to think about drawing as an important tool for slowing down and really seeing.

Schmidt also took students from various disciplines on sensorial walks into the small pockets of forest on the UBC Vancouver campus, exploring how our senses allow us to slow down enough to build a relationship with the natural world. She encourages educators to take the time to immerse their students in their environment—reflecting on what they see, smell, and hear—as a way to begin to incorporate an artistic perspective into their teaching.

“Once you do that kind of immersion work, then I think it’s possible to pick up on so many different ways of responding,” she says. “That could be through creative writing or drawing. I know drawing can seem a little bit daunting for some, but the kind of drawing exercises that I do with students are very simple. It’s more about recording and responding to what you’re seeing. It’s not about creating masterpieces.”

Pedagogy is a significant part of Schmidt’s work as an educator. She says her present-day commitment to the natural world and her desire to contend with climate change were shaped by her childhood experiences in nature.

“Having time even just to play and to explore in the natural world, it opens up a whole world of learning,” she says. “It may not exactly check all the boxes in a [traditional] curriculum, but I feel like it’s the source of so much potential learning.”