by Chelsea Kowalski • Photos Courtesy of Patrick Wells

Patrick Wells has spent the past 28 years teaching high school science, working with rural communities in Newfoundland, and fishing for cod on the weekends. As a strong proponent of student ownership and student engagement, he became a PhD candidate in Professional Learning at Memorial University to learn even more about student education practices. He spoke with Root & STEM about his perspective on how to implement ocean conservation in the classroom and why inclusivity is an inherent part of education.

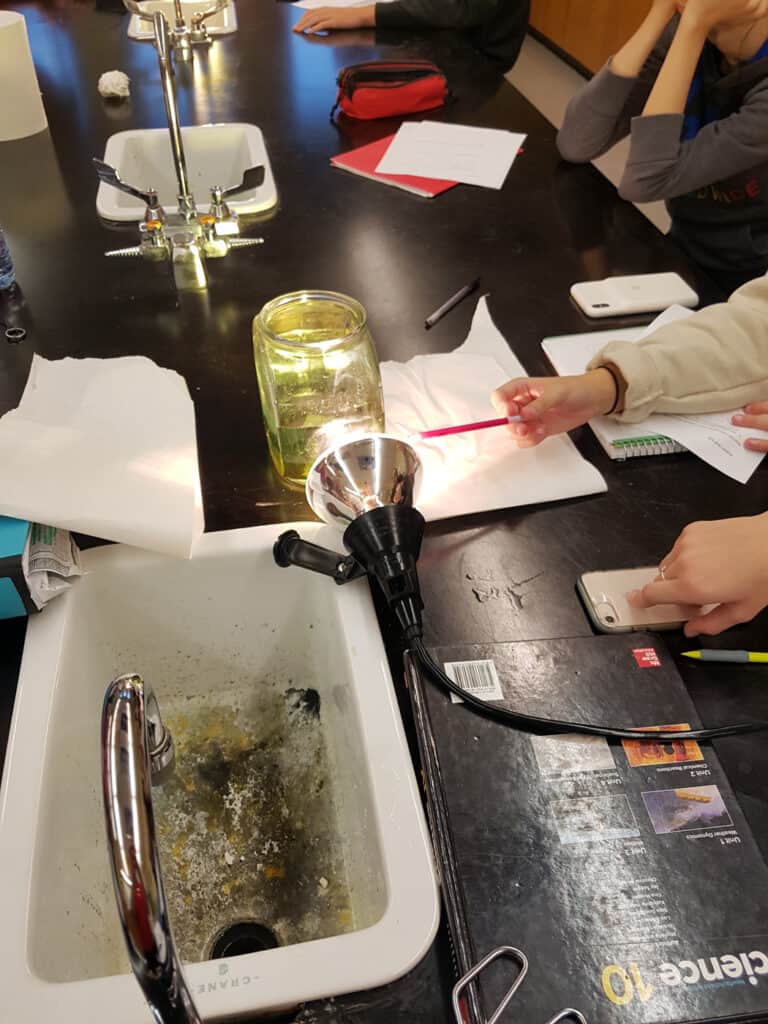

It’s been pretty easy here. We have quite an intimate relationship with the ocean in Newfoundland. Getting conversations started is one thing, but doing educational things is another. There are no fisheries that have never been overfished. We’re not being sustainable with these populations. You can get into the reasons for that with the students by asking them questions. We have done things with a pond on school property that has sticklebacks and students can do a “mark and recapture” to keep track of the population. Local knowledge is also really important to bring in. For example, fishers know that if it’s harder to catch fish, there are probably fewer of them. We’ve had major fish kills here on the island the past couple of years. When several million fish die, it’s tantamount to an oil spill, because of all the oil in their bodies that gets released when they decompose. You can create a conversation around that: Why did it happen to many fish in one place? Excess oxygen consumption? Higher ocean temperatures because of the changing Gulf Stream and more warmth on the south coast?

Additionally, you can try to get students to bring their own stories forth by having things in your classroom that are from the ocean, like shells. The learning becomes more personal, because it connects with their experiences and their family’s experiences. It’s more complicated to make those personal connections with students. You can’t do it by just standing in front of a class.

It’s a funny thing. I was not a fan of STEAM in the past. But I was involved with a project for which I created a painting of my dog. (I’m really quite proud of it.) I learned you can express data as art. There are activities I’ve done in the past, like having students go out to the pond and find items to put under the microscope so they can draw them and make a food web. We put up the students’ art and they drew animals or insects on big sheets of paper and we decided where they were going to go in terms of the food chain and what they eat and all these great conversations were generated. So is there a place for art in STEM education? Absolutely. And it’s about making that personal connection. Everybody loves to see their stuff up on the wall. They always take great pride in it. Especially for younger grades. It’s really important to get them to make that cross into art because sometimes they will have trepidation about science. But if you can contribute with art, which everybody can participate in, then that is a good first step to becoming a part of the science that you’re doing.

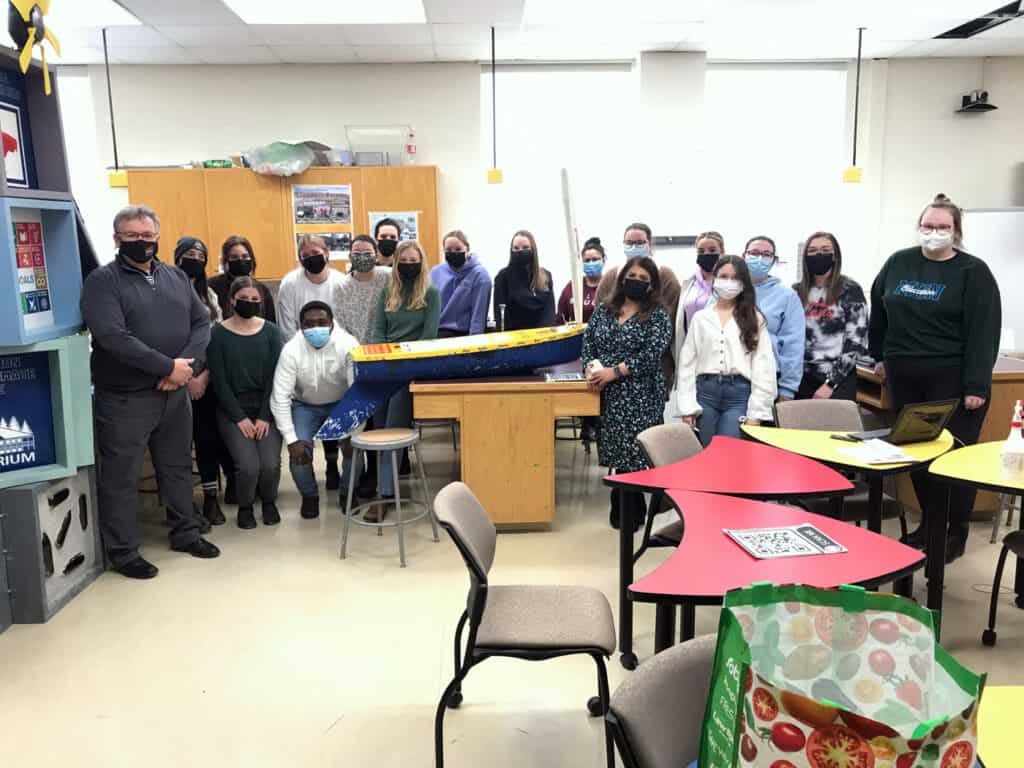

It’s hard to start because you’ve got to commit to trying, and people are uncomfortable with making mistakes. You need to push beyond that boundary. The students won’t get upset with you. It is invigorating for students to do something fresh. You really have to flip the whole discourse to have the students do the work. They’re generating the knowledge, and you’re there beside them asking formative questions. There are students who need you to take the time. That’s one of the things I realized when I was doing my reflective writing. I was doing activities, but I wasn’t reaching everybody.

One of the things I encourage people to do is ask students to make predictions, either publicly or privately. You can get them to write it down and ask why they made those predictions. You’ll get a conversation. When somebody makes something personal, like a prediction or a drawing, those are the real moments. They create memories. And we’re in the memory business.

Engagement is really important. The more you know about somebody, the better you can talk to them. So, you’ve got to find out what’s going on. And students are going to have bad days. But if you don’t watch how they think, it’s going to be very difficult for you to teach them. Students are the ultimate source of your knowledge as a teacher. You need to watch them and see how they respond. The look on their face, the tone of their voice, even if they’re not making eye contact with you, can help you evaluate what’s going on. Those types of things are really important in all classes, particularly in science, to find those people who are afraid of the subject. My prolific use of Play-Doh is the great equalizer because at first you’ll see a whole bunch of snowmen and snails, and then you get down to what you really have to do.

Confidence is a tough one. But if you love it, you gotta go for it, right? And don’t be afraid. Try a science fair project. Visit places like research facilities or aquariums (like the Petty Harbour Mini Aquarium in St. John’s) and meet with the people who work there. It’s a great place to go learn stuff, but also just ask them personal questions. Talk to fishers. You hear a lot of very interesting things over the cutting table when you’re coming in from fishing, and actually, sometimes really interesting research could be done. There are all kinds of monitoring stations all around the world where you can just go look at what research scientists are doing, like from Environment Canada and Oceans Network Canada. The Canadian Network for Ocean Education and the Canadian Ocean Literacy Coalition have all kinds of resources on their websites along with challenges that you can do.

Part of education is teaching students about people who have differences in mobility or senses. You need to put people in groups and mix them up so they can learn about other realities. And I tell them to focus on what they can do, not what they can’t do. It’s about getting out there and getting away from your lecture podium. Google Docs, for example, can be printed in braille. But that alone doesn’t mean your course is inclusive. Class discussions and group notes won’t be included in that and they are a big part of learning. You can’t say “I’m a teacher now and I’m going to put it in park.” If you do, you’re in the wrong business.

Touching, smelling, listening. Those are all important things. And learning has to be multi-sensory. Hearing the click of a beetle outside can be a lesson about scaring off predators and the students learn because they hear the click and they themselves get scared. But unless you’re outside, you’re not going to learn about what’s around and how to protect what needs to be protected.

The STEAM Makers section of Root & STEM showcases the different ways educators engage with students and promote STEAM concepts in and out of the classroom. If you know of an educator who goes the extra mile, tell us about them at STEAM@pinnguaq.com.