By Dave McGinn • Photos Courtesy of Lucid Inc.

Aaron Labbe was in his second year of studies at SUNY Fredonia’s School of Music when he suffered a mental breakdown so bad it caused a heart arrhythmia. He was rushed to hospital, where he spent three days in intensive care and nearly a week in the cardiac unit. Doctors initially thought Labbe had a heart issue. Then they misdiagnosed his case again, telling him he suffered from panic disorder.

He was prescribed the antidepressant Zoloft, a decision that would have disastrous consequences: doctors didn’t realize Labbe suffers from bipolar disorder, which requires that Zoloft be taken with a mood stabilizer to avoid triggering episodes of mania.

“I spent basically two years in a severe manic state,” says Labbe, the founder of Lucid, a Toronto-based software company that uses music to help people with mental health issues.

Halfway through his fourth year at the conservatory, Labbe was briefly institutionalized. Thankfully, during his stay, a psychiatrist correctly diagnosed his condition. But doctors told him he would likely have a difficult life, going so far as to say he would not even be able to hold down most jobs. He cycled through a range of medications before finding one that wouldn’t make him throw up. He found work at a Shopper’s Drug Mart, a job that came nowhere close to fulfilling his ambitions.

“I was longing to do something with my career,” Labbe says.

Music had always been his dream. And, after what he’d been through in the mental health system, he now had a goal for what he wanted to do with it.

“I decided I wanted to dedicate the rest of my life to fixing the system that had done so much harm to me,” Labbe says.

Algorithm & Blues

Over the next several years, Labbe dedicated himself to understanding how music can be used to treat mental illness. While music therapy has long been used to help reduce anxiety and improve people’s sense of well-being, Labbe approached the subject as both an artist and an engineer. His results so far point to a promising option for people who are looking for an alternative to the mental healthcare system, and want treatments tailored to them as individuals.

“There are people who are suffering because they don’t have a better alternative to medication,” Labbe says.

Born and raised in Welland, Labbe didn’t discover music until he was 13 years old. His parents had divorced, and he was living with his mother in Buffalo, New York.

“I was lucky enough that the school district had a really good music program,” he says.

Labbe was drawn to drums and other percussion instruments, especially the marimba. He eventually earned a degree in music production and audio engineering from the conservatory, despite continuing to struggle with his mental health.

Looking back on the breakdown that changed his life, Labbe says it was preceded by years of various mental health challenges, including anxiety and difficulty balancing his mood. After he’d been correctly diagnosed and had decided on the course of his career, he enrolled in Ryerson University’s new media program, where his interest in applying his arts background to solving science and engineering problems was heavily encouraged.

The collaborative nature of the program meant Labbe was able to learn about neurology and artificial intelligence while working with peers from a wide range of fields, including biomedical engineering, which became a key component of Labbe’s work.

“I think art and technology intersect a lot of times in ways that we don’t really think about,” he says.

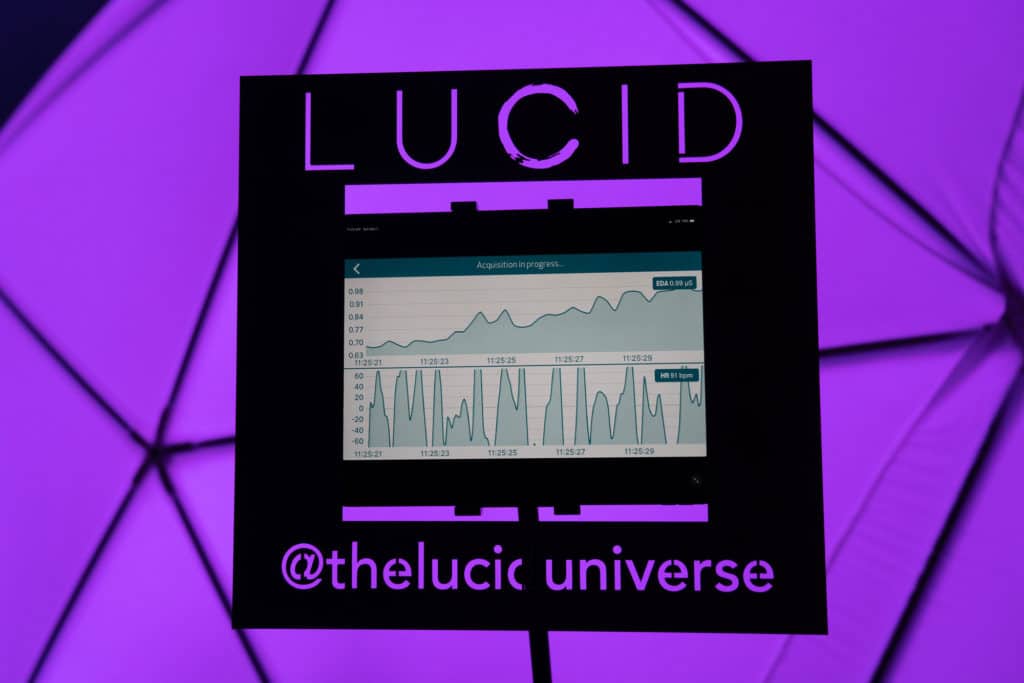

He called his thesis project Lucid, a name inspired by wanting to help people’s thoughts become clear. In this model, users lie down inside a small geodesic dome, wearing headphones and an electroencephalography reader (EEG), a device that records brain waves, on their forehead. Soothing light appears on the dome, and music begins to play, with layered ambient sound.

The key, however, is an algorithm Labbe created, which plays different music and ambient sounds in direct response to the user’s brain waves. The result is a completely individualized experience.

The algorithm, Labbe believed, held the promise of helping countless people who suffer from anxiety. As he explains it, Lucid’s technology creates a “beat frequency” that syncs with a user’s brainwaves, then slows them down, helping to soothe and calm a racing mind.

With the Lucid prototype complete, Labbe toured art galleries to test its potential.

“I kind of treated the art gallery as a lab,” he says.

Lucid’s ability to bridge art and science is clear from the range of venues that have taken an interest in the project. For example, both the Ontario Science Centre and Nuit Blanche Toronto, an annual celebration of contemporary art, have commissioned Lucid exhibitions. In 2019, Labbe took the installation to Europe, where Lucid won the prize for Startup of the Year at the Wallifornia MusicTech event in Brussels. (A full list of Lucid’s past exhibitions is available on their website.)

As more and more people experienced Lucid, the results were “overwhelmingly positive,” Labbe says. Yet, while the project clearly seemed to help reduce their anxiety and improve their overall mood, there was still one major problem: if Labbe wanted as many people as possible to benefit from Lucid, he would have to find a way to deliver the experience in a much more accessible way than a travelling installation that could only accommodate one person at a time.

Good Vibes

When it was incorporated in 2017, Lucid was just Labbe and the company’s co-founders, Zach McMahon and Zoe Thomson. With the company formalized, the trio dove into research and development work, to figure out how to scale the fundamental experience of Lucid and make it easily accessible to a large number of potential users. Today, Lucid employs a dozen people, including engineers working on machine learning, cloud computing and musical composition. But it would take the team nearly two years to solve the scalability problem. The solution, an app called Vibe, was launched in January 2020. Vibe strips Lucid down to its core elements—and, in several ways, improves upon it. While it is designed to help people with a range of issues—it promotes better sleep, sharper focus and improved energy levels—its main focus is helping to alleviate anxiety.

“We’re trying to build a product that can provide intervention, wherever you are,” Labbe says.

Users begin by indicating their current mood on a grid that suggests various emotions and psychological states, such as sad, bored, worried, excited and tense. The app then creates a personal playlist composed of nature sounds recorded with a binaural microphone and mixed with layers of music to create an immersive, spatial audio experience for the listener. The app also offers personalized playlists of short clips of music from across genres, layered with auditory beat stimulation—a technique that uses particular frequencies to create an “aural illusion” that operates at the same bandwidth as the electrical activity in our brains. The tones that are generated may have the ability to help induce certain mental states, and to reduce anxiety in particular.

When the music has finished playing, users are once again asked to enter how they’re feeling. By capturing this information, the app is able to learn how effective it was. The more a person uses it, the better the app understands what kinds of music work for them.

“It’s a machine learning system that basically measures your responses to music and learns what musical features work best for you,” Labbe explains. “It makes getting to relaxed states much easier.”

Theoretically, he says, someone could use the app to be soothed by thrash metal, or any other music of their choice. In its current incarnation, Vibe doesn’t have any heavy music.

“But once we get other content licences going, this will become a possibility,” Labbe says.

Connections

Since the Vibe app was launched in January 2020, more than 7,000 people have installed it on their devices. Data collected by Lucid shows just how successful the app has been.

“We’re decreasing anxiety on average by 60 per cent. We’re increasing positive emotions by 55 per cent. It’s working,” Labbe says.

To better understand just how effective Vibe is, a pre-clinical study involving 120 people who suffer from anxiety is currently being conducted at Ryerson University. When that study is complete, Lucid will conduct a randomized control trial of 150 study participants in conjunction with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

“In order for us to change the system, we have to work from within it,” Labbe says.

Having the added credibility of these studies that demonstrate Vibe’s effectiveness will also help it stand out in a burgeoning marketplace. Worldwide, the mental health apps market accounted for US$587.9 million (about C$770 million) in 2018. It is expected to grow to nearly $3.9 billion by 2027, according to the market research company Absolute Markets Insights.

Lucid’s current target demographic is people who are using technology to help themselves with health issues, Labbe says.

“Particularly 18- to 32-year-olds. That group tends to use apps to optimize their life,” he says.

It’s no wonder many people in that age range and others are turning to apps to help with their mental health. By age 40, nearly half of everyone in Canada will have or have had a mental health condition, according to the Canadian Mental Health Association. At any given time, between 25 and 30 percent of people have mental health issues. Most have low-severity anxiety and depression, says Dr. Farooq Naeem, chief of General Health Systems Psychiatry at CAMH and one of Lucid’s advisors.

“For those people who have the low degree and severity of those kinds of problems, this is quite remarkable,” he says of Vibe. “You can address the mental health needs of a large number of people through this sort of platform.”

Indeed, people who suffer from anxiety typically face two main difficulties, Naeem says. One is that people who want to get treatment from a therapist usually face waiting lists that can be months long.

“We don’t have many therapists. We don’t have many mental health professionals,” Naeem says. “Even in a big city like Toronto, we don’t have many therapists to help people.” That lack is amplified in rural and remote communities, where the number of options may be more limited.

The other problem is that many people don’t want to seek out a therapist, whether because they can’t afford to do so, or they feel that the stigma is still too great, despite changing social attitudes. Marginalized communities may feel even more hesitation, fearing institutional bias or racism.

“We have plenty of evidence to suggest people prefer interventions where they don’t have to see a mental health professional,” Naeem says. He believes anyone facing either limited access to, or concerns about, in-person counselling could benefit from using Vibe to address mild anxiety. In an age of physical distancing, amid concerns about an impending mental health crisis in the wake of COVID-19, a mobile, musical tool for mental health seems tailor-made for the moment.

Learning Music

There is a long tradition of using music therapy to improve mental health. Indeed, several studies have shown that it can be used to reduce generalized anxiety disorder in children, helps reduce levels of depression in cancer patients, improves the quality of life for people with dementia, and decreases the perception of pain in people with short-term pain and those suffering from chronic arthritis, among many other benefits.

But what makes Vibe unique, Naeem says, is that it’s constantly learning a person’s preferences so it can adapt itself to deliver a customized experience.

“Any kind of intervention is more effective if it is individualized,” Naeem says.

Labbe, who experienced what he calls a “we-still-know-better-than-you-do” attitude during his time in the mental health system, wants the products he and his team make to be as individualized as possible. He’s particularly interested in how wearable technology could add to customization, and if it could be used to gain other biomedical indicators, such as a person’s heart rate.

While he and the team at Lucid are currently concentrating on helping people with anxiety, Labbe believes the potential for using music to address health issues is endless. Next, he hopes to see if Vibe or something similar could be used to help people with depression. He’s also curious to explore how his company’s melding of art and technology could be applied to people living with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“What we want is to be a medicinal music company,” Labbe says. “We want to see how far music can go, in all facets of health.”