Indigenous Leadership for Conservation and Reconciliation

By CarolAnne Black

The Birth of Tribal Parks

The Tla-o-qui-aht Nation’s territory extends from one of the few remaining ancient temperate rainforests down to the Pacific Ocean. It is a place of thousand-year-old cedars up to 4 metre in diameter. Elk run through the misty woods, and black bears catch salmon as they migrate upstream, pulled back to rivers and streams by an unstoppable urge to spawn the next generation where they themselves hatched.

All of this remains because, to stop the proposed clear-cut logging of Wanačas Hiłhuuʔis (Meares Island), in 1982 the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation declared it a Tribal Park.

Bringing the small island tucked into the coast of Vancouver Island under Traditional Law, the Tla-o-qui-aht began the successful protection—through advocacy, litigation against the British Columbia government, and blockades—of the island, their territory, and their people.

In 2014, they took the concept of Tribal Parks even further. After the treaty process with the BC government had failed twice, “our chiefs and Elders at that time declared the entirety of our traditional territory a Tribal Park and added three more land designations: Ha’uukmin Tribal Park, Esowista Tribal Park, and the Tranquil Tribal Park,” says Terry Dorward, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation who worked for the Tribal Park at that time.

In creating the Tribal Parks, the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation both protected their lands and reasserted governance over their traditional territory.

Tallurutiup Imanga, Tuvaijuittuq, and Conservation at Your Doorstep

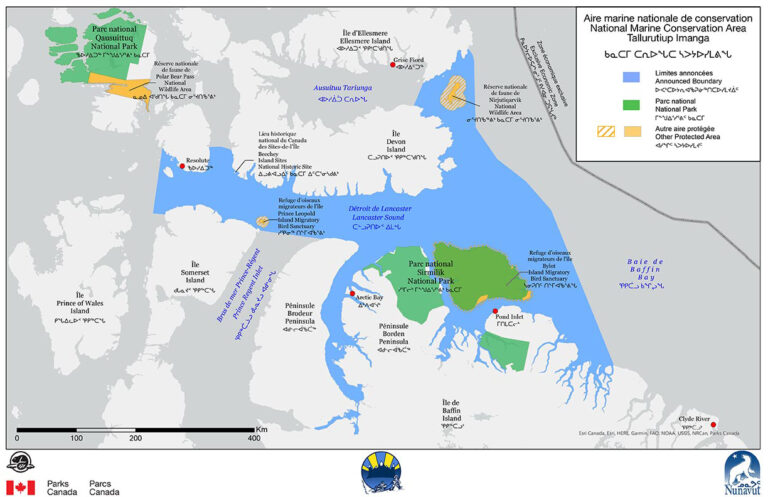

Thousands of kilometres northeast of Tla-o-qui-aht territory, in a place so different as to be absent of trees, a process to develop Inuit co-managed conservation came to fruition in 2019. The resulting Tallurutiup Imanga Inuit Impacts and Benefit Agreement (IIBA) and Tuvaijuittuq Agreements created, by a staggering margin, Canada’s largest marine conserved area.

Tuvaijuittuq, north of Umingmak Nuna (Ellesmere Island) and home to the oldest and thickest sea ice in the Arctic, covers 319,411 square kilometres (5.55 per cent of Canada’s marine area), and is 28 times larger than the next-largest Marine Protected Area. Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area (Lancaster Sound) covers 108,000 square kilometres (1.9 per cent of Canada’s marine area) and is an area of central importance to the Inuit of the Qikiqtani Region (Baffin Region).

“For Inuit in the region, Tallurutiup Imanga is at the heart of our conservation goals,” says Richard Paton, Assistant Executive Director for Marine Wildlife Conservation at the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA). “It’s the bridge that connects our northernmost waters in Tuvaijuittuq all the way down to our southernmost waters in Hudson Bay. Inuit are not a stationary people. We historically, and even today, move great distances, and we move because we follow the wildlife.”

Beluga whales travel as far north as Tallurutiup Imanga, and have their spring birthing in the waters of Hudson Bay. Caribou migrate through the Qikiqtani Region not only seasonally, but in cycles of seven and seventy years. For QIA, which represents Qikiqtani Inuit, negotiated the IIBA, and co-manages Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq, conservation means maintaining the environment such that, after 70 years away from Qikiqtani, caribou can come back.

“We conserve [the land] because of Inuit cultural continuity—our ability to transfer knowledge from generation to generation and access to the wildlife that we rely on and have relied on for millennia. We understand and relate to the dynamic relationship we have with wildlife,” explains Paton. “Migratory birds like geese, waterfowl like ducks and eider; or [species] in the marine environment that include Arctic char, turbot, beluga, narwhal, seal, or on the terrestrial environment that transitions out of the marine, like polar bear, caribou, fox, or wolves. Those are all species we actively look to conserve.”

Three Qikiqtani communities (Resolute Bay, Pond Inlet, and Arctic Bay) are located on the shores of Tallurutiup Imanga, with two more (Grise Fiord and Clyde River) nearby. The communities benefit from the conservation area for travel, camping, fishing, and harvesting the marine environment. They also bring back freshwater from ice caps and glaciers.

“We undertake [these activities] as a people because we’re living and breathing in the waters that surround Tallurutiup Imanga. Inuit are a part of Tallurutiup Imanga,” says Paton.

Inuit leaders first spoke out for conservation measures when resource extraction loomed. In the 1960s, oil and gas exploration was beginning in the North. The possibility of an oil leak into the water where they harvest was unacceptable. Paton says those first conversations about conservation gained momentum into the 1970s, when Inuit first began proposing the creation of Nunavut as a territory.

With the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement of 1993 (and the creation of the territory of Nunavut in 1999) came the concept of IIBAs, which included the stipulation that Inuit would benefit from activities in their territory.

The Four Moose Narrative

As a signatory to the 1992 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, in 2015, Canada adopted Aichi Target 11, a target for the protection of biodiversity. The country had agreed to protect at least 17 per cent of its land and inland water and 10 per cent of its coastal and marine areas by 2020. The Government of Canada recognized that to reach this target and in a way that honours reconciliation, they would need to work with Indigenous Peoples.

“[Justin] Trudeau’s government brought me in, and it was a little weird, I have to say, in the beginning,” says Eli Enns, who worked alongside Terry Dorward at the Tribal Parks, and co-founded Tla-o-qui-aht’s Ha’uukmin Tribal Park.

In the spirit of reconciliation, The National Steering Committee asked Enns to create an advisory body made up of Indigenous Experts and government representatives, which would eventually become the Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE), to provide recommendations for meeting Canada’s conservation targets.

Enns’s role also meant partnering with various levels of government and representing that partnership with Indigenous Nations. Enns told the committee, “If you’re looking for a token Indian in this process, I’m not the right guy for you. Respectfully, I said to them, ‘If you’re looking for somebody to help sell a watered-down version of Tribal Parks to First Nations across Canada, I’m not the right guy for that job either.’ And I honestly thought they weren’t gonna call me back.”

He received a contract offer the next day.

Due to his experience with the treaty process between the Tla-o-qui-aht people and the BC government, Enns continued to test the waters of good faith. “Before I can go public with you in our relationship,” he reports saying to the committee, “I need to clear the air on the elephants in the room.” Then he identified the four things he knew Indigenous communities would need before they would consider developing their own version of Tribal Parks or conserved areas. Enns got the responses he needed.

By the time ICE’s final report, “We Rise Together,” was published in 2018, the elephants had been replaced and these key pieces to working with Indigenous Nations in conservation became known as the Four Moose Narrative. “The Four Moose Narrative is a memory device; it’s a story,” says Enns, relating it to the oral basis of many Indigenous cultures and the critical importance of memorable stories and concepts in transmitting information between people and generations.

Courtesy of QIA

The Four Moose are:

The “We Rise Together” report has been credited with catalyzing the concept of the IPCA in Canada and providing a way for Canada to move forward with reconciliation and reach its conservation goals.

Outsized Conservation and a Shift to Self-Governance

In 2022, Canada upped its conservation goal to what’s known as “30 by 30”—30 per cent of land, inland water, and ocean area conserved by 2030. The prime minister also announced up to $800 million to support the creation of four IPCAs using a funding model based on partnerships between Indigenous organizations, governments, and philanthropic interests. QIA is one of the four selected Indigenous organizations.

For QIA, Paton says that the process of creating and co-managing Tallurutiup Imanga catalyzed Inuit-led conservation. Now, “Inuit leaders have said, for conservation space to occur, it needs to be done through an IPCA because then Inuit leaders are coming forward with the ability to conserve as opposed to having it legislated and Inuit being told: ‘This is an area that you will conserve on behalf of Canada.’

The Qikiqtani Region spans 13 communities of which only five are adjacent to or nearby Tallurutiup Imanga; QIA’s goal in creating more conservation space is to reach all of their communities. QIA is proposing an Inuit-led governance model for the new conserved areas, in which the government still has a role but final decision-making lies with the Inuit. Under this agreement, government-run parks and migratory bird sanctuaries within Tallurutiup Imanga would also eventually transition to the new governance model.

The new areas they are seeking to conserve focus on Qikiqtait, which covers the waters surrounding Nunavut’s southernmost community, Sanikiluaq (the Belcher Islands) and Sarvarjuaq (the North Water Open Polynya).

How much conserved area does this represent? The population of Qikiqtani comprises 16,500 Inuit and just under 21,000 people in total, or about 0.003 per cent of the Canadian population. Under QIA’s proposal, the total area to be conserved is one million square kilometres; equal to 10 per cent of Canada’s total area, and one third of Canada’s 2030 conservation target. “For a very, very, very small percentage of the Canadian population,” says Paton, “we are conserving approximately 33 per cent of Canada’s intended total target.”

Guardians and Stewards of the Land

Enns says if he could have it his way, all of Canada’s newly created conservation areas would be IPCAs. But, he disagrees with the concept of conservation to protect just a fraction of our environment.

“All of this still stems from a worldview of disconnectedness. We’re going to create a park for nature over here and an industrial sacrifice area for the economy over here; in the same watershed, no less. So both the conventional protected area and the industrial sacrifice area stem from the same worldview of disconnectedness, which primarily sees human beings as separate from nature.”

Terry Dorward says that, in the past, 10,000 people lived in the Tla-o-qui-aht rainforest and it remained intact. Dorward sees IPCAs as an expression of Indigenous Peoples regaining autonomy, stepping outside reserves and upholding their roles and responsibilities, “including measures of conservation on how we as Indigenous people see it.”

“In Tla-o-qui-aht, for example,” says Dorward, “when we did our watershed planning, we changed the concept of ‘land use’ to ‘land relationship’ because we felt [the utilization of the land] was just kind of a one-way approach.” In discussion with Elders, to address areas impacted by poor logging operations, tourism, and other factors, they made a plan to restore these areas, and include a small human activities footprint. They also set out no-go zones. Called Qwa-siin-ap, the idea is to leave the area alone for the animal world, in particular because the strain on bears, elks, and other animals is increasing. This change in land relationship is also a return to traditional ways; entire communities once moved to let Chims (bear) hibernate in peace.

Courtesy of Terry Dorward

To implement their land relationship plan, Dorward helped to create and launch the Tla-o-qui-aht Guardian Program in 2009. “Guardians are the front lines for the hereditary chiefs, ensuring traditional laws are upheld.” They also work in the restoration of rivers that have been degraded by unsustainable logging practices, the revitalization of salmon habitat, environmental monitoring, the removal of derelict vessel and marine debris, and recycling, trail maintenance, and other improvements. More recently, Guardians have taken on acting as guides and ambassadors, helping visitors understand who the Tla-o-qui-aht people are and how they can become allies, which includes encouraging them to take the ʔiisaak Pledge, setting an expectation that visitors “carry themselves with dignity, honour, humility, and respect.”

In Tallurutiup Imanga, the Nauttiqsuqtiit Inuit Steward Program is evolving as the Inuit move toward self-governance. Paton says this year will be the first when the research priorities for monitoring Tallurutiup Imanga’s waters, sea ice conditions, and wildlife will be set entirely by the Inuit Stewards, who conduct that research. They are also responsible for harvesting marine animals and sharing their catch with the communities, community engagement and youth mentorship, gathering Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit knowledge) and traditional skills from Elders, and search and rescue. Just like the Tribal Park Guardians, they act as cultural liaisons.

As the IIBA is implemented, physical infrastructure continues to be put in place, supporting the Stewards. This year will see the start of the development of multi-use facilities, which eventually will be built in all five affected communities. These facilities include “a place where the Stewards can store their skidoos or their boats or have a place to distribute country food to community members, a place for them to do their reporting, and a place where Elders can gather and share information with our Stewards.” The communities are also set to receive small-craft harbours, which, in places with little to no physical infrastructure, will give them a safe haven for their boats in the summer.

With Hope and Commitment Comes Change

Now, Enns and Dorward work for the IISAAK OLAM Foundation, an educational not-for-profit Enns co-founded to address the Capacity Development Moose. One of their many projects, led by Dorward, is delivering a fully accredited IPCA planning certificate that is associated with Vancouver Island University. Through the certificate program, they are reaching people across the country and around the world who are interested in developing IPCAs.

Enns says the main goal of IISAAK OLAM is sharing good practices quickly as they emerge, “because we’re in a time crunch. The real time crunch is the survival of our species and for us to be better at managing our relationship with nature. But the artificial time crunch is the 30 by 30 goal.”

Enns is endlessly hopeful that we can meet all our conservation and reconciliation goals, and save the planet. At the start of 2024, Canada stands at having about 16 per cent of its land and water areas protected. In the next six years, that number needs to double.

“I know a lot of people are feeling hopeless these days, and we really want people to be hopeful because when we turn that light on, that’s a prerequisite to achieving the things that we need to accomplish. So, I want people to feel hopeful and to believe.”

Dive into a world of imagination with our downloadable colouring page featuring an old-growth forest with towering trees.

If you need inspiration, you can check out the artist’s original version on page 32 of the “Climate Conscious” Spring 2024 Issue of Root & STEM. So grab your favorite markers or crayons, and get ready to bring this magical scene to life!