by CarolAnne Black

Alex Flynn grew up fishing for lake trout with his dad through a hole cut in the ice. Out on the lake, he was supposed to be jigging—bobbing his fishing line up and down to entice the trout to bite. But Flynn, a member of NunatuKavut and of settler ancestry, spent much of his time as a child lying on the ice, peering down the hole hoping to see a trout bite the hook. It was a terrible way to catch fish, Flynn notes, and a great way to get cold and wet. At the end of the day, Flynn and his dad would bring their catch to his grandparents’ house. His grandmother would prepare the fish for dinner and visitors to the house would go home with gifts of trout.

Flynn has since left Forteau, the 400-person fishing community he grew up in on the South Coast of Labrador. Now a master’s student at Memorial University in St. John’s, he brought his fishing knowledge forward when he joined a team studying lake trout populations in Labrador: “It’s what I grew up with; it was related to my home.”

Alex out on the ice

Alex’s dad holding his catch

For his studies, Flynn began reviewing previous research on lake trout. He noticed that most of what had been written about lake trout came from regions outside Labrador. Most strikingly for Flynn, the knowledge he had grown up with was absent.

Lake trout are widespread across North America, but Labrador’s populations live in a different environment and climate than others. The climate in Labrador is relatively cold and, most significantly, Labrador’s waterways are made up of a vast system of small, shallow lakes connected by rivers and streams. Flynn says Labrador’s landscape “creates more isolation and makes little pockets of [trout] populations.” This, Flynn explains, is different from large lakes, where fish populations interact continuously and so generate more genetic diversity. And more genetic diversity means the populations can be more resilient to climate change. To understand Labrador’s lake trout better, and to be able to support their conservation, we need to know not just about lake trout in general, but what is particular to Labrador’s populations.

Flynn and the team of researchers set out to determine if the fish were moving among the lakes. They sequenced the DNA of 559 trout samples donated from fishers from 35 lakes. Since interacting populations have closer DNA structures, Flynn says with their data, “you can see which populations are more similar or different.” The results can help answer questions like: Where are fish travelling? Are they travelling upstream or downstream? What are the barriers for trout moving among lakes? Are barriers caused by people, climate change, or nature (e.g. a waterfall may limit travel to one direction)?

Throughout his project, Flynn was working to increase our knowledge of the lake trout particular to Labrador; but he still felt like the accepted methodology of science meant the knowledge he had grown up with couldn’t be included. All that changed, however, in early 2020, when he became a lab technician at Memorial University’s Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR).

CLEAR is an anti-colonial feminist lab situated on the ancestral homelands of the Beothuk. Its website states, “Our methods foreground values of humility, equity, and good land relations. We’re working to do research differently.” CLEAR’s work focuses on the environmental monitoring of plastic pollution. CLEAR researchers survey beaches, skim surface water, and analyze bird and fish guts, searching for plastics. The results tell us what types of plastics and how much are getting into the environment and into animals’ digestive tracts.

Flynn says that if something doesn’t fit within the values of CLEAR, they find another way. Max Liboiron, the director at CLEAR, describes those values as being baked into everything CLEAR does, from taking out the trash to deciding who is named as first author on a paper (which can affect an academic career).

The team at CLEAR maintains good land relations in several ways, which includes how they work with communities. Liboiron says, “CLEAR begins a relationship with a community by co-creating research questions. It then has the community hire co-researchers, who are paid by CLEAR and who bring their own knowledge and expertise.” The lab will only publish data if the community consents. CLEAR also has samples analyzed by someone from those lands. In Flynn’s case, he handles samples provided by Inuit communities that are part of projects sponsored by the NunatuKavut Community Council, because he is from the lands where the samples were collected.

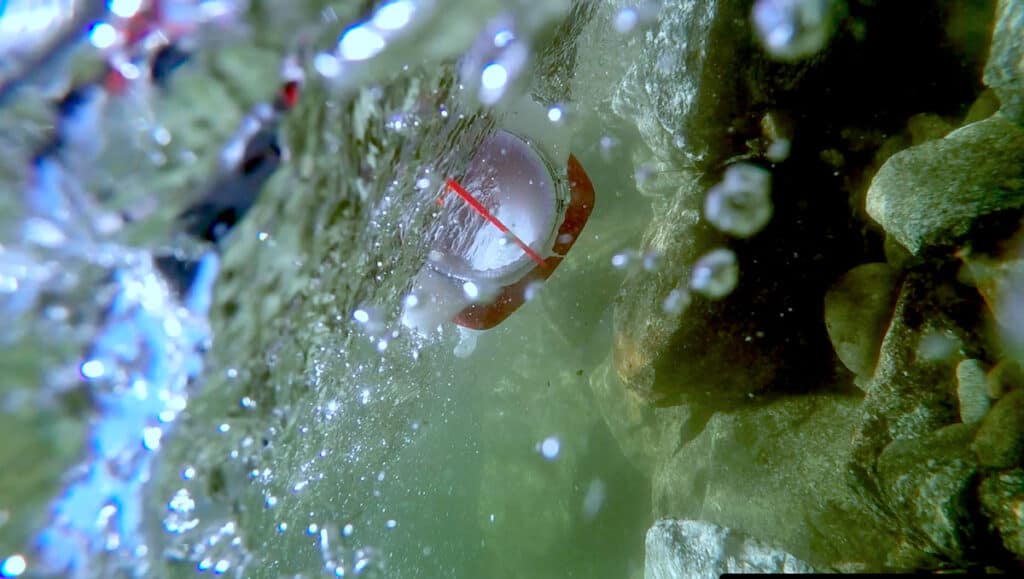

To make research more equitable, CLEAR develops measurement instruments that can be built in a garage. BabyLegs, for example, skims surface water to collect small particles and is made of baby tights, pop bottles, and other easy-to-find materials. Liboiron says that developing technology, like BabyLegs, “means all sorts of people can do monitoring who couldn’t before.”

Now, Flynn is bringing CLEAR’s principles into his research on Labrador’s lake trout. “Working with CLEAR made me want to highlight more non-standard forms of knowledge. I want to use more local and community sources of information. When I talk to my dad, to my grandparents, to anyone from down home, they tell you how important it is.”

Flynn knew there was knowledge missing from the picture of lake trout in Labrador because he could see the gap. Ensuring that any research conducted includes community members from the research location benefits not only the results but what we can learn moving forward.

Resources

To learn more about CLEAR’s Research Methods, check out the following videos.

Guts

A short documentary film following Max Liboiron and CLEAR through their methods of practising science.

Laboratory Life: Author Order (Episode 1)

How do we ensure that the process by which authors are credited on publications is not only transparent but equitable, and are able to recognize the full range of labour that goes into scientific work?

Laboratory Life: How We Choose Our Values (Episode 2)

How do we choose which values and goals we align with as researchers? This film shows how we chose those values through storytelling, consensus, and deliberation.

Laboratory Life: How We Run a Lab Meeting (Episode 3)

Meetings can be brutal. Or they can enact humility and accountability. Lab meetings are the central way that CLEAR lab transforms lab members from a group of individuals into a collective. This film shows how we run lab meetings so they fill us up, rather than drain us.